When we learn about Diatonic Modes, or as some call them, the church modes, we are told that those modes are scales on a degree of a major key. While this is true, it doesn’t actually give us a clue on how to use them or why it is even important to know about them.

It is all very well and good that we know each degree by name, but what do we do with them?

That is one of the questions that I will address in this post, while I explain the various modes. We will combine the theory with the practice so you can know how useful these modes really are.

At the end of this article, you will:

- know what diatonic modes or church modes are.

- be able to build the scale of each mode.

- have a good idea of the musical feel of each mode.

- have a better understanding of how to use them.

As a special bonus, I have added a downloadable chart of the sequence of chords for all the modes… You will find it at the end of this article!

The Traditional Way Of Explaining Modes

Because it is interesting to know where the modes come from it is best that I explain modes according to how they are taught by most tutors out there. It is helpful because you will be able to relate the modes back to their major key.

An added benefit to instruments like guitar, this way of explaining the modes offers ways to associate modes with positions on the neck of the guitar, which is a fantastic help in getting to know your fretboard. That will inevitably enhance your soloes.

Each Major Scale Has 7 modes

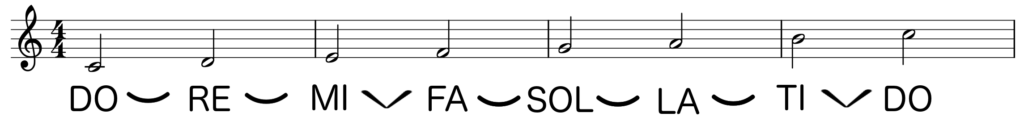

In western society, we learn, from a very young age, to sing a major key from the root note all the way up to its octave. The most natural major key is the one in Do (or C) because it only contains natural notes:

This is the most common form in which the major key is used as most songs are written in this scale.

Imagine though that you sing the exact same notes, but you start from the second-degree note, the Re. In the same way, you could start from the third-degree note, the Mi. What it boils down to is that you could start to play or sing that major key from any of the seven degrees.

Each of those scales that start from a different degree in a major key was given a name.

Modes are also often described by a formula to show how the intervals change when compared to the Ionian mode with the same root, so I will give you the formula for each as well.

I will explain more about what they are and how to use them further down in the article so hang in there! 🙂

Ionian Mode

Degree: 1

Formula:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Example in the key of Do major (or C major) – the Do Ionian mode aka C Ionion mode:

Dorian Mode

Degree: 2

Formula:

| 1 | 2 | b3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | b7 |

Example in the key of Do major (or C major) – the Re Dorian mode aka D Dorian mode:

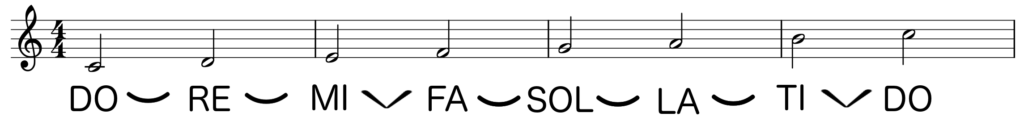

Phrygian Mode

Degree: 3

Formula:

| 1 | b2 | b3 | 4 | 5 | b6 | b7 |

Example in the key of Do major (or C major) – the Mi Phrygian mode aka E Phrygian mode:

Lydian Mode

Degree: 4

Formula:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | #4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

Example in the key of Do major (or C major) – the Fa Lydian mode aka F Lydian mode:

Mixolydian Mode

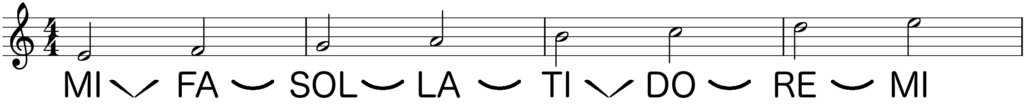

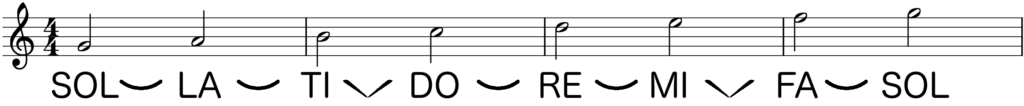

Degree: 5

Formula:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | b7 |

Example in the key of Do major (or C major) – the Sol Mixolydian mode aka G Mixolydian mode:

Aeolian Mode or Minor Key

Degree: 6

Formula:

| 1 | 2 | b3 | 4 | 5 | b6 | b7 |

Example in the key of Do major (or C major) – the ‘La Aeolian mode’ aka ‘A Aeolian mode’ aka ‘A minor key’:

Locrian Mode

Degree: 7

Formula:

| 1 | b2 | b3 | 4 | b5 | b6 | b7 |

Example in the key of Do major (or C major) – the Ti Locrian mode aka B Locrian mode:

But What Can We Really Do With That Information?

It is nice to know how these modes are formed and it is great to know that they are related to a major scale. But how does this really help us when playing our instruments?

Where does this add value over knowing the major scale very well with the sequence of triads, tetrads and their respective arpeggios?

There are a few things that are helpful with this method of explaining the diatonic modes.

Find the Key Signature Of Any Given Mode

When somebody tells you that a piece is written in D Lydian, you now know that Lydian is the mode on the 4th degree of some major scale. So in order to get to the key signature of this major scale, we count back a perfect 4th interval and arrive at A.

And we know the adjusted notes in the key signature of A major are F#, C# and G#.

Guitar Player Benefits

Guitar players can use this to help out with improvisation.

When a song in the key of A major for example and there is a chord of C#minor7, a guitarist will know to use the Phrygian grip with a C# in the root. And if they know their arpeggios in that grip very well and the avoid notes… They are well on the way to play a great jazzy solo, without the need to resort to the pentatonic scale.

No Other Benefits That I Can Think Of

Besides those two benefits, I can’t really think of anything else that this traditional method of explaining modes has to offer.

If there are other benefits, please do let me know in the comment section below as I may be overlooking something truly awesome. 🙂

I would almost say that if this was the only way of explaining modes, they would practically be useless for pianists. But there is more to diatonic modes which will become clear in the next section.

A More Useful Way Of Explaining Modes

The most important difference from the traditional method is that we stop looking at modes from the perspective of their related major key. Rather we will look at each mode played from the same root note and focus on the changes in the patterns of intervals towards that root note.

Patterns and interval change greatly determine the mood of a song and this is where the modes’ usefulness really comes to fruition.

That sounds more complicated than it really is so let’s dive in to remove those question marks.

Diatonic Modes or Diatonic Moods?

What the traditional method fails to show is that diatonic modes are actually the stuff that determines the mood of a song.

Everyone knows a major key creates a happy mood and a minor key creates a sad mood. But are we ever ‘just’ happy or ‘just’ sad? What about in-between moods? Ecstatic, bored, down, elated, crushed, hopeful…

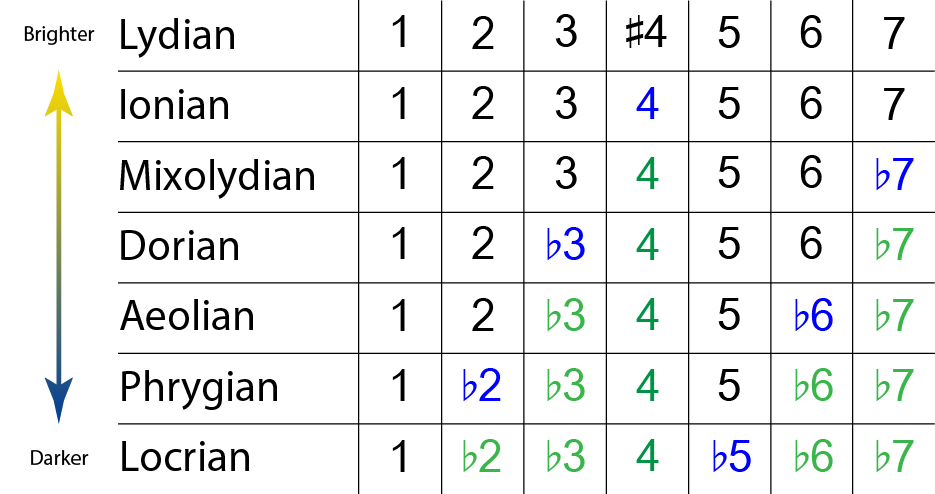

Overview From Brightest to Darkest Mood

When it comes to a mood in music, what really is the determining factor are the intervals from each degree to the root. If the big (major) intervals are in the majority the mood will be brighter, if there are more, small (minor) intervals, the mood will be darker.

We can sort the different modes according to this idea as we show here in this image:

We can see here that the Lydian mode has the most, big intervals. I am deliberately not saying ‘major intervals’ because #4 is actually a tritone and not a major 4th. It is, however, bigger than a perfect 4th.

After that, we notice that each subsequent mode alters one interval to become smaller when compared to the prior mode:

- Ionian gets the perfect 4th

- Mixolydian flattens the 7th

- Dorian flattens the 3rd

- Aeolian flattens the 6th

- Phrygian flattens the 2nd

- Locrian flattens the 5th

Important to note that because these modes are so closely related, it is very easy to modulate or transition between these modes and create smooth changes in the tonality of your song.

Remember this the next time you are looking to write your bridge in a different tonality from your main theme!

The Sound of Diatonic Modes aka Church Modes

I will illustrate the sound of diatonic modes and what mood they bring about, with some songs I have put together in MuseScore.

I tried to stick to the same type of melody so it is easier to detect the mood changes. However, this was not always possible due to the introduction of avoid notes in some cases.

Nevertheless, I do hope this gives you a nice idea and an overview of setting the mood using the various modes.

Disclaimer: The examples are not intended as full modal compositions but serve to illustrate how similar melodic material might sound when expressed in different modal colours.

True modal music would use very typical chords for that specific mode. I will dedicate a post on that in a future article.

Lydian Sound and Mood

The Lydian mode sounds light and elated even though the #4 introduces a tritone with the root, it works very nice with the major 7 chord at the first degree of this mode; turning it into a major 7 #11.

The Lydian scale is the favourite scale of many movie and theatre composers because it can be used to create those grand, end of movie climactic ecstasy that makes your heart explode with joy when everything works out in the end.

I will dedicate a whole article on the Lydian mode soon because it is such a beautiful and widely used mode.

Here is a sample in C Lydian. Notice that the I – II – V – I progression in Lydian mode are all major chords.

Ionian Sound and Mood

The Ionian sound is very familiar to us since it is no different from the major scale that we all grew up with.

One thing to notice is that the 4th note is an avoid note when playing the major 7 chord at the first degree of this mode. Often when improvising over a first-degree major 7, musicians will borrow the #4 of the Lydian mode because it sounds very nice.

In this case, I wanted to keep things pure Ionian as that was the aim of this exercise so I took the 4th-degree note down to a 3rd-degree note instead.

Here is a sample in C Ionian. Continuing on the I – ii – V – I progression, notice that we now have a single minor chord.

Mixolydian Sound and Mood

The last of the major modes, the Mixolydian mode gives me somewhat of a blues feeling. It sounds very dominant since the Chord on the first degree is a dominant 7 chord that is left unresolved.

This sample is in C Mixolydian and continues on the I – ii – v – I progression. We now have two minor chords in that pattern.

Dorian Sound and Mood

With the Dorian mode, we venture into the minor modes. It sounds a bit sad, but more of a disappointed sad. Not an ‘I cry my heart out’ kind of sad.

This sample in C Dorian still continues on the i – ii – v – i progression. All chords in that progression are now minor chords, which does explain the sad mood.

Aeolian Sound and Mood

The ‘cry my heart out’ mode is the Aeolian mode and it comes as no surprise that it is also known as the minor key.

The sample is, as you may by now be able to guess, in C Aeolian. It too continues on the i – ii – v – i progression and introduces a half-diminished chord on the second degree. That chord causes a sad and crushing tension into the overall mood of the song.

Phrygian Sound and Mood

With Phrygian mode, we enter into the realm of sad and creepy. However, in Spanish music like the Flamenco, it does not sound creepy at all and it is in that music that the Phrygian mode shines the most. The upheaving spirit of the Flamenco is because of the rhythm, awesome accentuation and seriously fast and virtuoso passages.

The Flamenco, however, is a whole new beast to be slain… Let’s stick to our more common western theory for now.

The sample uses C Phrygian and continues on the i – II – v – i. Even though it introduces a major chord again it sounds very dense because it is only a semitone above the root. You can get some nice effects with the Phrygian mode, but it is a scary mode that holds some trickery that you will need to get used to.

Locrian Sound and Mood

Now we come to the darkest of the church modes that we have available: the Locrian mode.

I should probably tell you upfront that this mode is not very attractive. It is hardly ever used and I can’t readily think of songs that use it, except for a fast solo passage over a half-diminished chord in a progression.

There is a very logical reason behind the reason it is not very popular. Every other church mode has a stable chord at its first degree. Each one of them has a perfect 5th interval which acts as a stable home base. We can come home to the first-degree chords on the first 6 church modes.

In comes Locrian and throws even that security overboard. Its 5th interval is a tritone; the most unstable interval of them all… It trumps even the flat 9. 🙂

Mind you, one can make some fancy horror music using tritones and flat 9s excessively… But that is yet another beast to be slain.

The sample continues with C Locrian darkness, using the progression: i – II – V – i. The introduction of the two major chords doesn’t really help to make the mood of this mode any happier.

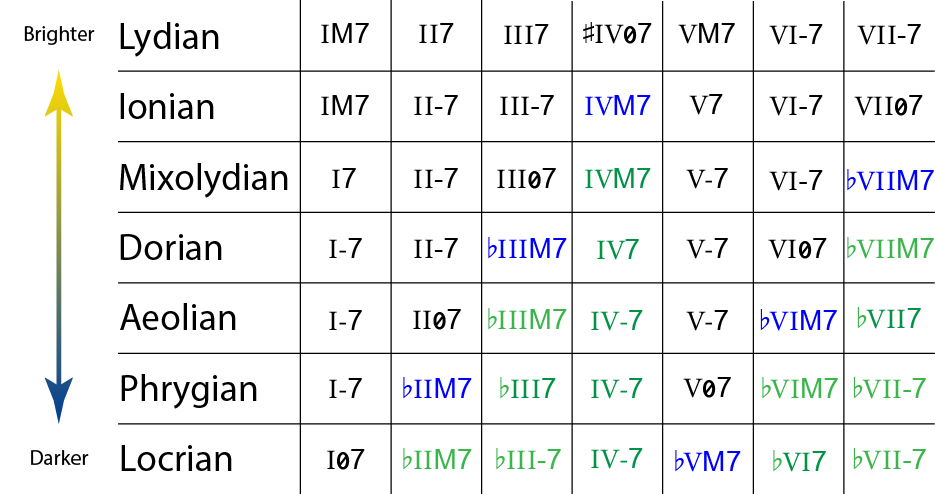

Modal Chord Sequences

Finally, I want to also give you this chart which shows the sequence of chords for each mode. It is in the same order as the previous chart and uses the same colour scheme.

I have made this chart available for download as PDF containing all vector graphics so you can print it as large as you want… Create a poster for the wall next to your bed if you want. 🙂

Conclusion

I hope that I was able to give some more insights into what diatonic modes aka the church modes are and how they can be applied in your own music.

It is now up to you to start creating songs with different moods and easy transitions from one mood into the other.

How will you incorporate the diatonic modes aka church modes in your songs?

My number one recommendation to learn the piano in a fun and hassle-free manner is a program called Flowkey. Go try it out for free ► https://go.flowkey.com/pianowalk

4 Comments

Thank you very much for this explanation!

But i can’t seem to download the PDF you linked.

Any chance you could send it to me?

Thanks for the message Jonas.

I have sent you an email 😉

Your website is fascinating! I’ve always wondered about the emotional response to music.

I get sad and disturbed when listening to early church music by Josquin de Pres or Ockeghen, which is modal (slightly dark modes?) but stay happy and engaged when listening to Byrd (Spem in Alium is wonderful) My husband says he finds the first two composers soothing, but I have to leave the room after about 20 minutes.

As a contrast J S Bach is my idea of music that makes me thrive … almost medicinal! Accept of course, the Passions but they are essential Easter listening. .

Thanks for your comment Judy!