In this post, you will get acquainted with everything you need to know about key signatures. That is useful when you need to know which notes to play in any given key and for both major and minor scales.

You may be wondering what a key signature is? You can hover with your mouse over the underlined word, and you will see an explanation from my glossary… However, that is a typical Wikipedia explanation.

I believe that while reading this article, you will get a much better idea of what key signatures are.

If you are not yet sure what a major scale is then I urge you to go read my post about the major scale:

► Piano Scales: The Major Scale

In this article, I speak about the perfect fourth and perfect fifth intervals. If you are not sure what those are please refer to my post about intervals:

► Music Theory: Intervals – How To Train Your Ears

What is a Key Signature?

In short, a key signature is a group of either flat (♭) or sharp (♯) symbols that usually appear at the start of the staff, right after the clef. This group of symbols defines in which key the music is written.

You will see that it is repeated at the start of each staff on your score, whenever the clef is drawn. In principle, this is not necessary because the same key signature is implied during the entire song until a new key signature denotes a change in tonality.

If a key signature shows an F♯ for instance, this means that whenever we see an F on the score, you should always play F♯ instead. Always, unless it is preceded by the natural symbol (♮), in which case – as you may expect – you would play a natural F.

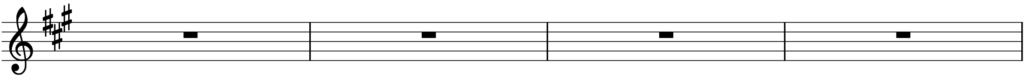

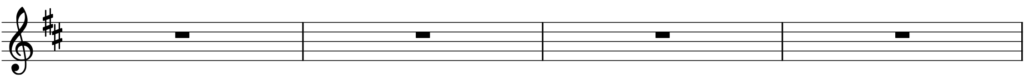

Example of a Key Signature

In the above staff, we see a group of three sharps (♯). F, C and G.

I can already tell you that this is the key signature of A major or its relative F♯minor but don’t worry about how I know this, the goal of this article is to make sure you will be able to do this on your own.

Characteristics of Key Signatures

The most notable characteristic of key signatures for major keys and their relative minor key is that symbols never mix.

What I mean with that is that a group of symbols will either be all sharp symbols or all flat symbols. You will never see a key signature that has both flats and sharps.

The second most notable characteristic of key signatures is that the symbols always appear in the same order. I will elaborate on the order in the next section.

Learn all about keys and signatures in a practical and interactive way.

Start your free trial here ► https://go.flowkey.com/pianowalk

The Order of Symbols

It almost sounds like a knighthood, but alas…

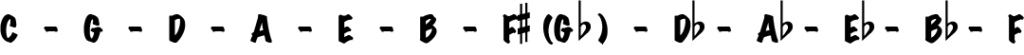

The Order of Sharps (♯)

First in note names:

Then in alphabetical letters:

To remember this last one, there are some nice acronyms out there. Check out this website for examples…

My favourite acronym is for sure: Foxy Cheerleaders Get Dates After Every Ball Game

So sharps always appear grouped in the same order:

If the key signature has

- One sharp then that will be the F♯

- Two sharps then those will be F♯ and C♯

- Three sharps then those will be F♯, C♯ and G♯

- Four sharps then those will be F♯, C♯, G♯ and D♯

- and so on…

You should also notice that the interval between the notes is always a perfect fifth:

F# to C#, C# to G#, G# to D#, etc.

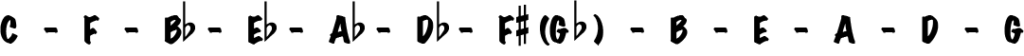

The Order of Flats (♭)

They appear in reverse order of the sharps and so…

First in note names:

Then in alphabetical letters:

My favourite acronym is for sure: Blanket Exploded and Dad Got Cold Feet

Again for more examples, check out this website.

So flats always appear grouped in the same order:

If the key signature has

- 1 flat then that will be the B♭

- 2 flats then those will be B♭ and E♭

- 3 flats then those will be B♭, E♭ and A♭

- 4 flats then those will be B♭, E♭, A♭ and D♭

- and so on…

You should also notice that the interval between the notes is always a perfect fourth:

B♭ to E♭, E♭ to A♭, A♭ to D♭, etc.

The book has been around for quite some time and has tought many people all the Essentials of music in a very clear and fun way.

Click on the images to find out more at Amazon.

How To Build Key Signatures

There are two main methods to do this:

- Memorize the order of symbols and two easy formulas

- Using the circle of fifths

You could in principle also use the method I describe in my blog post about the major scale. But that is not something you can do ‘on the fly’ so while that method is excellent for understanding ‘why‘ there is a flat or a sharp note, it is not practical.

My personal preference is the first method. That is probably because it is the first one that I was taught a long time ago when I first started with music. Anyway, time to get to the beef!

Using Formulas and the Order of Symbols

A Few Rules of Thumb

- F major and C major are exceptions to all following rules

- If the key has no extra symbol in its name, the key signature consists of sharps

- If the key has a flat in its name (e.g. A♭major), the key signature consists of flats

- If the key has a sharp in its name (e.g. F♯ major), the key signature consists of sharps

Dude, this is not getting any easier, is it???

Trust me, it is not as complicated as you think.

Ok, so there are two possible scenarios for this, right?

- Either you have the signature, and you want to know the key.

- Or you have the key, and you want to know the signature.

So I will always explain things for when you have the key signature, and that should make it easy to figure out the reverse case.

The Formula for Key Signatures with Sharps

For any given key signature made up of sharps, take the last sharp and add a semitone to it to get to the major key name.

LAST♯ + 1 semitone = Major Scale Name

A Major Example

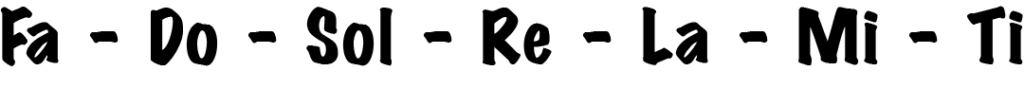

Let’s look again at the example from the start of the article:

It has three sharps in the key signature, and those are according to the order F♯, C♯ and G♯

So if we use the formula from above and we add a semitone to the last sharp:

G♯ + 1 semitone = A –> A major

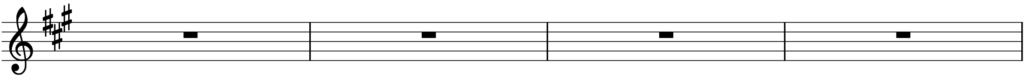

B Major Example

Let’s do another example:

It has five sharps in the key signature, and those are according to the order F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯ and A♯

Again we use the formula, and we add a semitone to the last sharp:

A♯ + 1 semitone = B –> B major

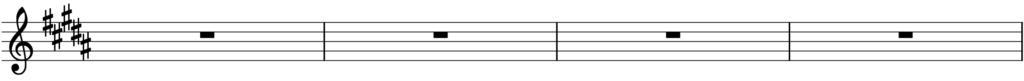

D Major Example

let’s do it in the reverse case where we want to figure out what is the key signature of D major.

The first thing to note is that D Major has no sharps or flats in its name so it belongs to rule of thumb number 2 and so we expect it to have a key signature composed of sharp symbols.

We can use the same formula except now we are looking for the last sharp rather than for the major key name.

Using some mathematical logic, we can use this formula instead:

LAST♯ = Major Scale Name – 1 semitone

And so for D major, we get: D – 1 semitone = C♯

Now knowing that C♯ is the last sharp we can apply the normal order of sharps and we kan tell that D major has F♯ and C♯ which results in:

The Formula for Key Signatures with Flats

For any given key signature made up of flats, take the second last flat, and you have your major key name.

No more no less!

That is an easy formula, and we will give you some examples to make it absolutely clear.

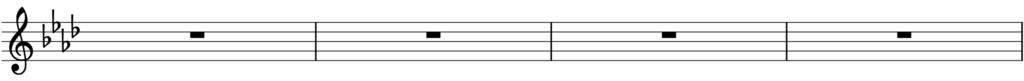

A♭ Major Example

Forget for a moment that you know the answer because you saw the title… 😀

We take the second last flat of the four flats we see B♭, E♭, A♭ and D♭, and we get to A♭ major

That is easy!

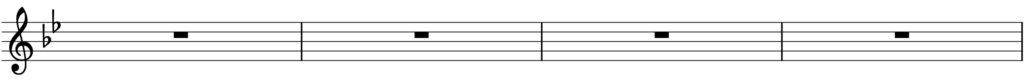

B♭ Major Example

We take the second last flat of the two flats we see B♭ and E♭, and we get to B♭ major

What if there is only One Flat?

Well, then we get into the exceptions of the rules of thumb number 1. If there is only 1 flat symbol in the key signature then you have to know we are in F major!

However, when you think deeply about it, that is not really an exception… And it may get a little bit too complicated, but bear with me.

Remember that I told you that in the sequence of flats, each next flat is a perfect fourth interval away from the previous one? Well, the first flat is a B♭, right? And what note would be a perfect fourth below that note?

If you said F then you would have been correct!

Using the Circle of Fifths

Ok, I would say that using the circle of fifths only for building key signatures is like using a firehose to water your plants…

There is so much more you can do with the circle of fifths, that I will dedicate an entire article about this nifty little tool.

It dates all the way back to the ancient Greek philosopher, Pythagoras. Yes, it is that guy responsible for all those formulas that we still use today in mathematics for trigonometry and all that jazz… (no pun intended).

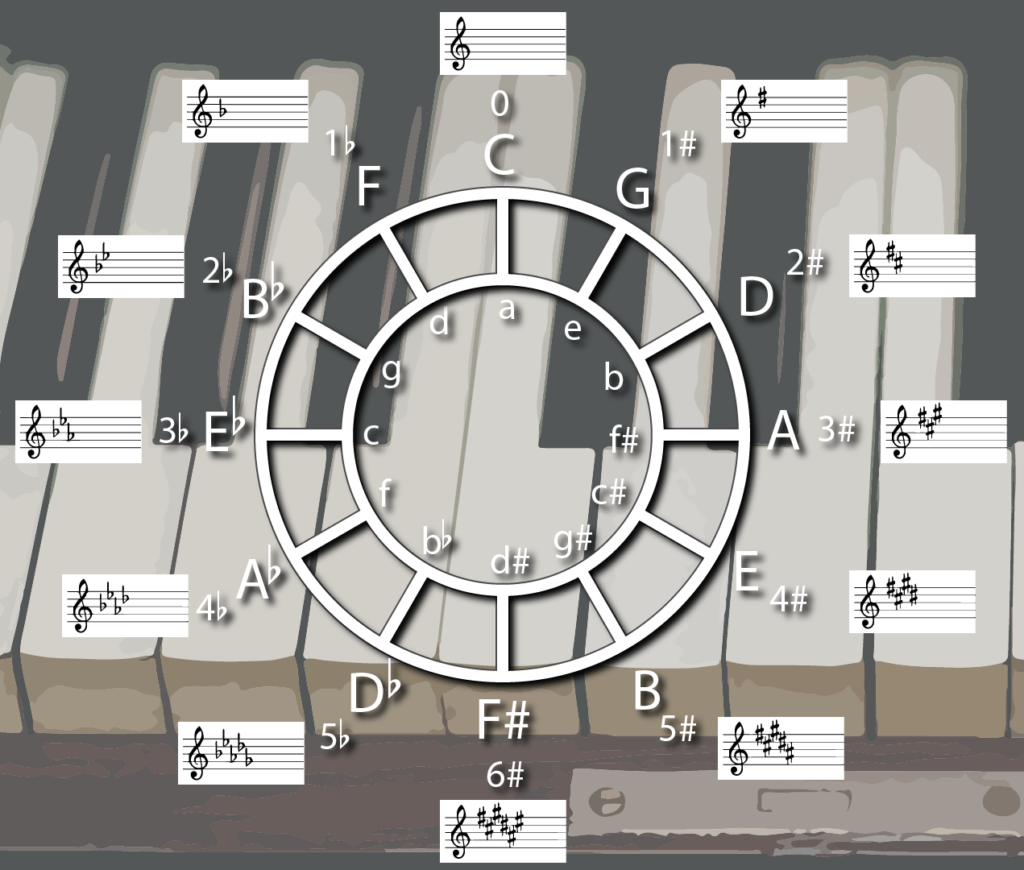

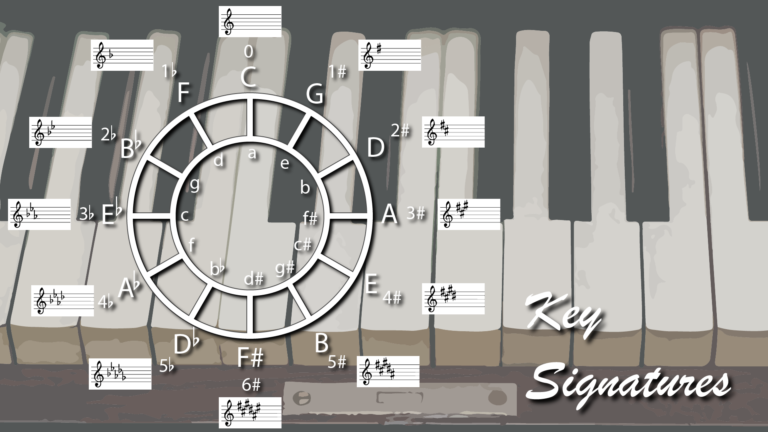

Basics of the Circle of Fifths

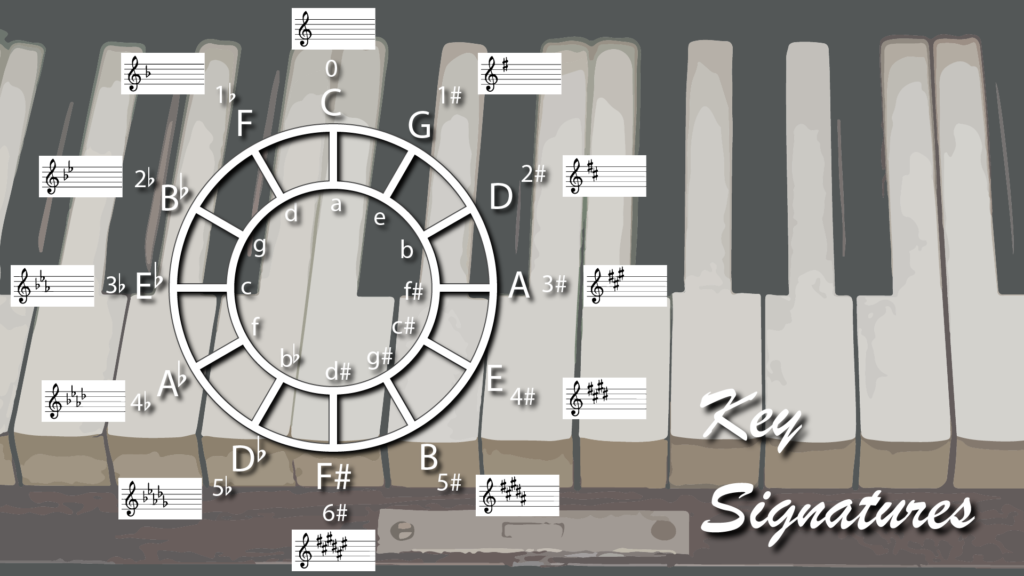

Have a look at the image above as it shows you a Circle of Fifths that I drew for you.

12 Major Keys and 12 Hours on a Clock

You may know already that there are 12 major keys in total… – Ok, you could argue that there are more – taking into account that there are some scales that have two names and two key signatures.

For example, we have F♯ major and we have G♭ major. Both are in fact the same major key but are referred to by different enharmonic notes. But when we forget about enharmonic scales, there are in fact 12 distinct major scales.

Incidentally, that is just the right number, so we can fit it on an analogue clock, which is exactly what was done when you look at the layout of the circle of fifths.

Click on the image to buy it at Amazon.

Clockwise all Perfect Fifth Intervals

When you traverse the Circle of Fifths in a clockwise direction you will find that every next note is a perfect fifth interval away from the previous note (exactly as the order of sharps we saw previously). You can now probably guess why they call it the Circle of Fifths? 🙂

Counter-Clockwise all Perfect Fourth Intervals

When you traverse the Circle of Fifths counter-clockwise, the fifth intervals are now in descending order and therefore become perfect fourth intervals (exactly as the order of flats we saw previously).

I just quickly want to mention that there is a soothing mathematical harmony in that fact… No wonder Pythagoras was so fascinated by this circle… I know… I am a bit of a nerd… Or a geek… Whichever you think is more suitable.

The Key Signatures on the Circle of Fifths

So now when you look at the image once more:

How to Deal With Sharps

When we start at the top where we have C major and we travel clockwise we see G major is at number 1 of the clock and has 1 sharp in the key signature. Likewise, D major is at number 2 of the clock and has 2 sharps. A major is at number 3 of the clock and has 3 sharps. And so on, and so on…

How to Deal With Flats

When we start at the top where we have C major and we travel counterclockwise we see F major is the first we encounter and has 1 flat symbol in the key signature. Likewise, B♭ major is the second one we encounter and has 2 flats. E♭ major is the third and has 3 flats. And so on, and so on…

The Enharmonic Major Scales

The three scales at the bottom on clock numbers 5, 6 and 7 are the enharmonic scales.

The B major could also be played as a C♭ major and following counterclockwise that key would have 7 flat symbols in its signature.

The F# major could also be played as a G♭ major and it would have 6 flat symbols in its signature.

The D♭ major could also be played as a C# major and it would have 7 sharp symbols in its signature.

It all Falls Back To The Order of Things

As you can see, whether you use the Circle of Fifths or not, you have to know the order of sharp symbols and the order of flat symbols either way. And as such, I think using the Circle of Fifths only for finding a key signature is a bit of overkill.

The Circle of Fifths, however, has a gazillion of more advanced uses, which I will address in a dedicated post sometime in the future. So keep an eye out for this post as it can be a major help when you want to harmonise and compose some awesome music!

Keep on walking the piano walk!

My number one recommendation to learn the piano in a fun and hassle-free manner is a program called Flowkey. Go try it out for free ► https://go.flowkey.com/pianowalk

10 Comments

Hello PianoWalk People,

I don’t know much about playing the piano, but it is a skill that I wish I had enough spare time to learn. This article overwhelms me a fair bit as it is very comprehensive, but it still comes across as a high quality piece of writing.

All The Best

SIMON

Hi Simon,

Thank you for your honest feedback!

I am sure that it can be a bit overwhelming. Feel free to ask me to for clarifications if you need any.

Cheers,

Tom

This is a great article. Thank you for the very thorough explanation and information on other helpful materials.

Hi Cynthia,

Thanks for your feedback!

Cheers,

Tom

Wow, this was a really informative article. I’m currently in the process of revising my understanding of the circle of fifths. I think I need to test myself without the use of an instrument in order for it to be most effective. To tell you the truth, I’m still struggling to see how I can apply it to improvisation, so I’m curious to hear what you have to say in future articles. Thanks

Hey Alec,

Thanks for your comment.

I will post an exclusive on the Circle of Fifths really soon. I intend to have some video material to support the article so it is taking a bit longer than expected.

One thing that I can tell you that will really help you to take improvising to the next level are upper structures, those are triad chords (or arpeggios if you play a melodic instrument like sax or flute) that you can play on top of the underlying chord progression. I will have an article about those in the future as well, but for now, do yourself a favour and search for them on YouTube!

Thanks again for your feedback!

Cheers,

Tom

Hi Tom,

This is a very good explanation for beginners and also intermediate who forgot!

I like the way you empower your readers to find out for themselves and not learn by heart.

Had I known this it would have helped me big deal. But I had to learn everything by heart and only understand how it worked later.

You have a unique, practical and engaging way of explaining. Thank you so much for sharing,

I will send my students to your website.

Great article!

Hi Janie,

Awesome! It is not an easy subject and often the explanations are overcomplicated so I am glad that this post comes across as practical and engaging.

I believe most teachers put far too little importance in training intervals because once you know intervals, most stuff becomes soo much easier to understand.

Cheers,

Tom

hey Tom! thanks a lot for putting this content out there! do you have any resources to recommend about the mathematical properties of the circle of fifths that you mention in this article? I feel that there is much more and I would like to read deeper!

Hey Alessandro!

If it is mathematics that you are interested in then I will assume you want to know more about what Pythagoras was so obsessed about?

Some articles that you may find interesting include:

https://www.phys.uconn.edu/~gibson/Notes/Section3_4/Sec3_4.htm

http://legacy.earlham.edu/~tobeyfo/musictheory/Book1/FFH1_CH1/1N_Pythagorean_Comma.html

I hope that gives some moe insights.

Cheers!