A lot of what was discussed in the article about Major Scale Chord Functions is also true for the Minor Scale Chord Functions and functional harmony in general.

One of the big differences in the natural minor scale aka the Aeolian mode is that the seventh degree is a minor seventh. It is a whole tone removed from the Tonic above and is therefore called a Subtonic rather than a Leading Tone.

In other words, the natural minor scale is missing a leading tone and with that, a strong pull back to the tonic. In order to fix that, the Harmonic minor and Melodic minor scales were created.

So when talking about chord functions and functional harmony in the minor scale we can’t forget about the Harmonic and Melodic minor scales. That makes this a very interesting journey.

What you will learn in this article is:

- why the Harmonic and Melodic scales were created to restore a leading tone in minor scales.

- the principles of functional harmony which is pretty much the same as for major scales.

- chord charts for all of these scales

- some common chord progressions

Evolution of the Minor Scale

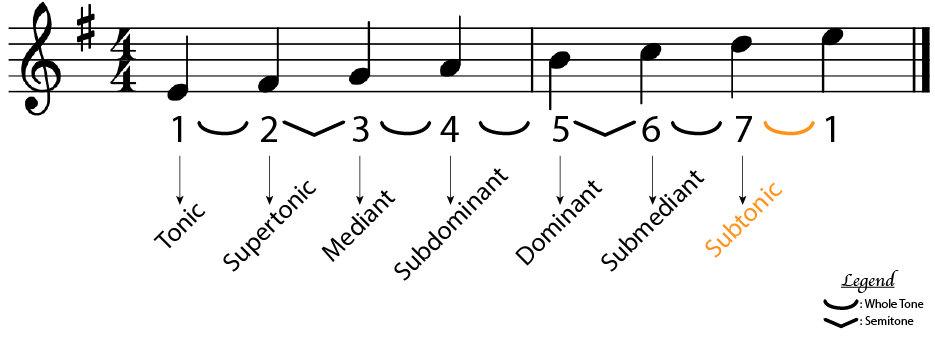

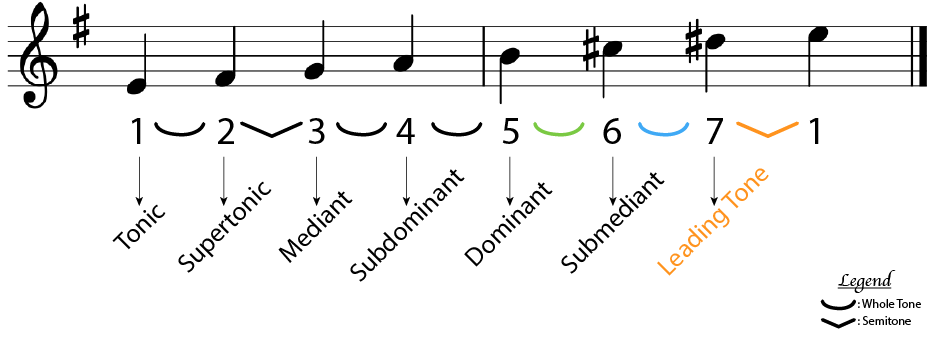

Like with the Major Scale, we number each note of the minor scale in ascending order. Those numbers represent the grades of the scale.

Naming the Grades of the Minor Scale

As we can see, most grades have the exact same function in the minor key as they have in the major key. The only exception is the seventh degree which is now a whole tone interval away from the tonic. For this reason, the seventh degree can not be used as a leading tone as it lacks the gravitational pull that a semitone has.

Flawed Dominant Function in the Minor Scale

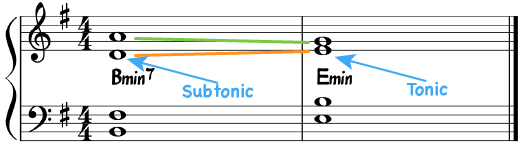

In this example in the scale of E minor, the dominant chord is Bmin7. When we layout these chords with particular voicings, we can use voice leading to create some expectancy to move towards the Emin chord, but it isn’t strong gravitation. It is also not a strong resolution because Bmin7 has no real tension that needs a release.

I used a rather typical chord voicing for the dominant chord Bmin7 to create a voice leading towards the tonic chord Emin. The top interval of this Bmin7 voicing is a perfect fifth so it goes without saying that this is a very stable chord with very little tension.

It is only through the voice leading of the D going up to the E and the A going down to a G that the Emin chord is expected. Have a listen and see if you agree:

Repaired Dominant Function in the Minor Scale

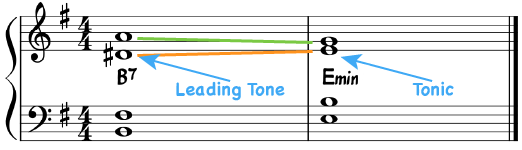

In an attempt to create more pull we could try to artificially make up a Leading Tone by elevating the Subtonic by a semitone. The Subtonic in the scale of E minor is D so let us change that to a D# instead. That would transform the minor 3rd of Bmin7 into a major 3rd and thus the chord is now a B7.

This example illustrates that artificial Leading Tone. It does two things in this progression:

- We now have semitone gravitation toward the tonic degree.

- We have a tritone interval in the voicing of our dominant chord that yearns for resolution.

Let’s listen to that progression. Hopefully, you will indeed notice that there is a lot more tension there that wants to be resolved by the tonic chord. And at the same time, it doesn’t sound artificial or strange in any way:

Harmonic Minor Scale: the Missing Leading Tone

This experiment, whereby we created an artificial Leading Tone, is nothing new. In fact, it was early Renaissance and Baroque composers that first tried this out. A missing Leading Tone meant missing tension and rather bland resolutions and that was reason enough to explore new things.

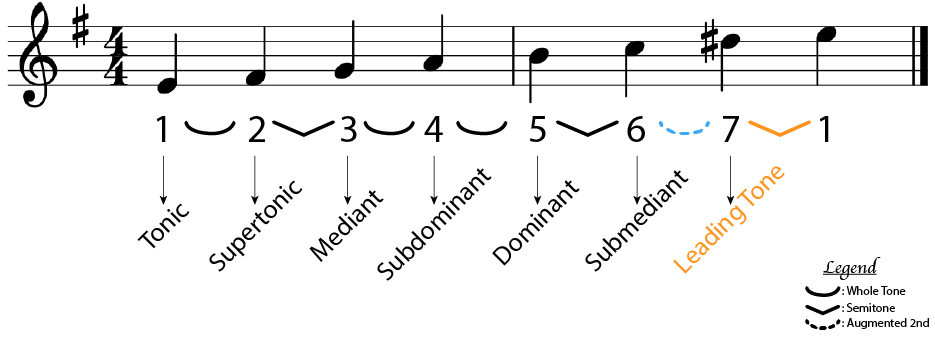

When we make this Leading Tone a permanent feature in a minor scale, a new scale is born: Harmonic Minor.

This created another caveat though; by elevating the Subtonic, an augmented 2nd interval is created between the Submediant and the new Leading Tone. During the Renaissance and Baroque era in Europa, the augmented second was considered an ugly and unsingable interval. It was something that composers would avoid at all costs…

We can suspect that there were some religious reasons for this dislike as well. The scale sounds very Middle Eastern and a span of 300 years near the start of the Renaissance is characterized by the Holy Crusades. The Harmonic Minor scale probably sounded too much like the music of the enemy in those days.

Lucky that we have evolved I might add 🙂 I personally really enjoy this interval and its middle eastern touch in the Harmonic minor scale.

I do want to note that this ugly augmented 2nd interval sounds exactly like a minor 3rd which was perfectly acceptable… It goes to show that the placement of intervals within a scale can completely change the way it is perceived.

Melodic Minor Solves Augmented Second

The solution to the augmented second interval was to also raise the sixth degree. Behold the birth of the Melodic Minor scale.

It created by Western European standards, a very natural sounding scale with the same harmonic functional prowess as the major scale.

But to retain some of the darkness of the natural minor scale there was some sort of an agreement that this scale would mostly be used for ascending melodies and that for descending melodies they would use the natural minor scale.

This ascending and descending rule was never set in stone though and it was often broken by many classical composers. Still, it is a rule that explains a lot of our classics.

With all of this shifting and elevating notes in the natural minor scale, we fully restored the harmonic functions that the major scale boasts. That means we can start using for a great part the same rules and common chord progressions in the process of composing songs in the minor scales.

I will follow up with the chord charts that go with these scales, but first I want to note something.

In a single song, a composer doesn’t need to stay within the same scale. A song could be written mainly in the natural minor scale and will often borrow chords from the harmonic minor or melodic minor scales with the same root note when the need (or the mood) arises.

It is very easy to jump naturally from one of these scales to another, given that you stick to the same root note (tonic).

Chord Sequence of the Minor Scale

With the addition of the harmonic and melodic minor scales, we have access to some very interesting chords like diminished, minor/major7, augmented chords… It creates a very nice and fresh soundscape at our fingertips.

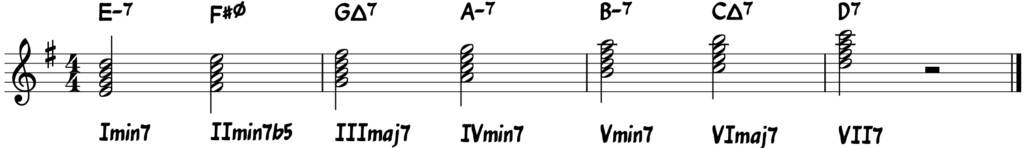

Natural Minor Sequence

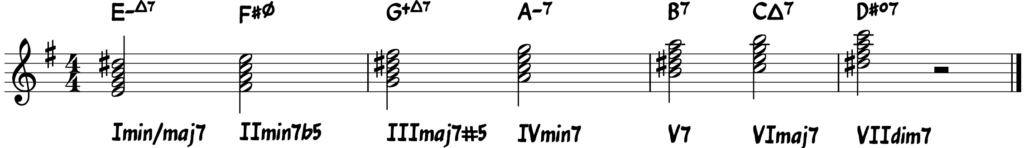

Harmonic Minor Sequence

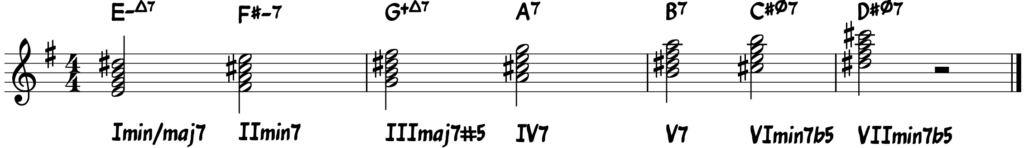

Melodic Minor Sequence

Common Chord Progressions in Minor Scales

In terms of functional harmony, all the grades and functions of the minor key are the same as the grades and functions of the major keys. Thus it makes sense that the common progressions in the major key would also apply in the minor key… And they do indeed!

The nice thing about the minor key is that you have a lot of options to borrow chords from the relevant harmonic and melodic minor keys and that means those progressions come in a variety of flavours.

I – IV – V

In this example, I wrote two similar phrases over pretty much the same chord progression. For the first phrase, I used the Vmin7 chord, which I substitute in the second phrase by the V7 chord which I borrowed from either the harmonic or melodic minor relative scales.

Classical musicians and theorists will tell you that this pattern of two similar phrases that repeat but end with a different cadence, is called a period in the realm of musical form.

Which scale, harmonic or melodic minor, ultimately depends on the notes in the melody and since I don’t use any type of C or C# in the melody over the B7 chord, it could be either one.

If someone would be playing a solo over this progression, they would be able to choose whichever scale they prefer.

I could also have substituted the IVmin7 with the VI7 from the melodic minor scale. Then it could make sense for the solo to use melodic minor over the IV7 – V7 progression. Ultimately though, one could pass quickly over melodic minor to harmonic minor and then back to the natural minor if one so chooses.

II – V – I

The most common progression in Jazz music, the II – V – I also works in the minor scale.

III – VI – II – V – I

Partly a II – V – I but we see this as a common progression on its own because it is really characteristic and often used.

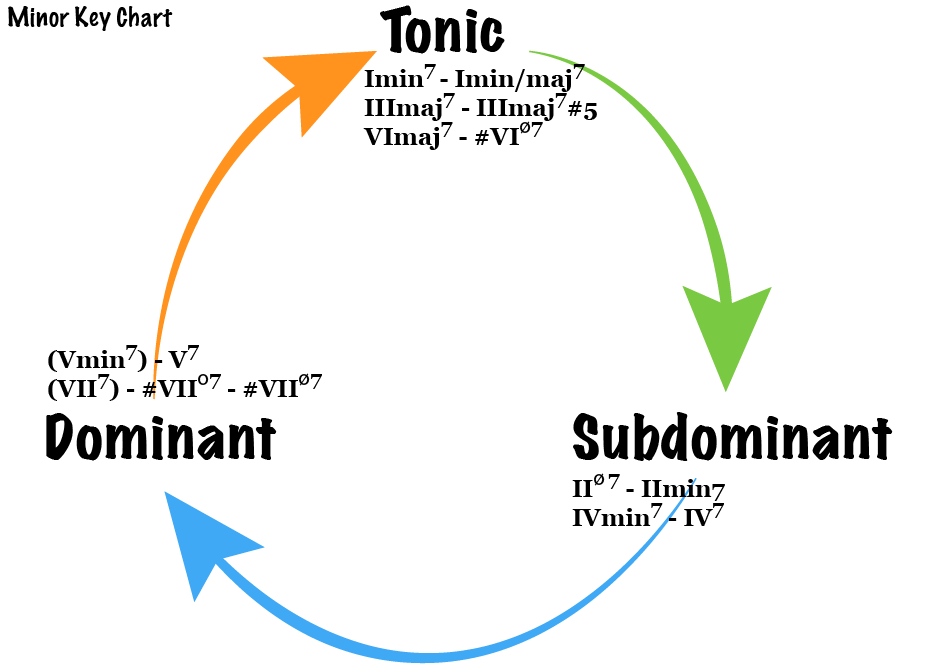

Common Function Cycle for Chord Progressions

The idea behind the Function Cycle for minor keys is the same as for the major keys… The dominant function of the chords in brackets is very weak but as we have learnt during the course of this article, the dominant function of those chords was restored by the introduction of the harmonic and melodic minor scales.

Next Steps…

There are other scales that sound awesome over the minor 2 – 5 – 1 progression. In a future post, I will highlight those with some examples.

Try creating your own progressions using the Common Function Cycle and create some nice music. I used free software to create the examples above, called MuseScore. Go check it out!

Functional Harmony and Chord Functions in minor keys will change the way you compose!

Keep walking the Piano Walk!

4 Comments

In the example about melodic minor with I IV V, I believe you meant to say substitute a IV7 for a ivm7, not substitute a VI7 for a vim7. Or am I missing something?

Same excuse here… Me messing up the Roman Numerals. :blush:

Thank you for your keen eye!

In your first common chord progression example, I VI V, I think you mean to say I IV V, given your chords of Em7 Am7 Bm7 and then substitutions of B7 and A7. Am I off base?

Oh my word, am I mixing up Roman Numerals again 😉

Indeed you are correct Charlie! Thanks for noticing.

I will need to update this.